Alexandra Biktimirova and Anastasia Karkotskaya, [former] Kazan residents and researchers, spoke with representatives of cultural institutions and the migrant labor community to find out if Tatarstan's policy of multiculturalism is effective and what are the reasons behind it.

“Kazan severs its friendship with Moscow!”

One of the most popular Tatar legends is the story of how the ruler of the Kazan Khanate, Söyembikä, refused to marry Ivan the Terrible. Later, when the city was captured, she jumped from the tower. Of course, there is no such theme in Sergei Eisenstein's Ivan the Terrible film. What's there is an incredibly theatrical exoticization of ethnic Tatars. The phrase in the title of this section is a script line from the Kazan ambassador, in response to which Ivan the Terrible announces a military campaign on Kazan.

In his documentary series about life in modern Russia outside Moscow, Tatar researcher Azat Akhunov argues that since the conquest of the Kazan Khanate, “Russian neighbors” have repeatedly violated the integrity of Tatar religion, culture, and language. The “conquest” of the Khanate was followed by mass displacement and forced Christianization: “If you do not touch religion, culture, and language, the Tatars will always be the best neighbors, friends, and colleagues of the Russian people. But if you interfere in these matters, the conflict erupts”.

Akhunov also says that the ethnonym “Tatars” was not used until the early 20th century, as it was considered offensive: people living in what is now Tatarstan called themselves “Kazan Muslims” or “Kazan Turks”. Nevertheless, by 1918 their desire for their independent state formation led to the creation of the Tatar Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic within the RSFSR.

During the period of glasnost, the public discussion about whether Tatarstan needed independence resumed. According to Akhunov, the main question was an economic one: why is all the money sent to Moscow and not left in the republic when there is a deficit? After all, Tatarstan is rich in resources (for example, oil). The same argument was used as the main reasoning behind the “Free Tatarstan” website, which appeared in July 2022, when it proposed holding a referendum in the republic.

Throughout 1990-1991, negotiations were underway to conclude a new union treaty, which assumed that Tatarstan would join the Union of Sovereign States on an equal basis with the RSFSR and other Union Republics. “If the GKChP had not happened on August 19, if we had had time to become a union republic when the USSR collapsed, we would have been able to leave and become independent. But we didn’t have time,” recalls historian Indus Tagirov, one of the authors of the Declaration on State Sovereignty.

As researcher Elena Gapova writes, “nationalist discourse began to be produced in explicit form during perestroika by certain groups of intellectuals. They articulated the interests of the emerging class) and, in some cases, the communist nomenklatura as well. Both subsequently became the heads of the new nation-states”. When [Mikhail] Gorbachev "got rid of the Marxist verbal shell, the only meaningful means of communication was the familiar language of nationalism".

Developing her argument, Gapova argues that “the very first space that could be treated as national, and therefore political, was culture <...>. Those who articulated the national idea usually defined it as freedom: freedom to know the truth about one's history (that is, to construct a non-Soviet version of it), freedom to read national literature (that is, to exercise censorship on other grounds), freedom to speak the national language, etc.”

Since 1991, Tatarstan's religious institutions of Islam and Christianity have been revived, and religious organizations have developed. Then, representatives of the international Tatar diaspora assembled the first congress, bringing them together. During perestroika, it became relatively possible to discuss interethnic inequalities, conflicts, and the dominance of one culture over another. There were scientific conferences on the policy of the Russian Empire to the autochthonous population of the Middle Volga region and political and economic regionalism in the USSR. At the same time, people organized demonstrations demanding political autonomy for Tatarstan and cultural freedom for the ethnic groups living on its territory.

Along with the processes described above, the “Kazan phenomenon” raged in the city — the name given to the youth and adolescent criminal associations that appeared in Kazan during the late Soviet period and later spread to other cities in the region. Among the leading causes of the "phenomenon," researcher and publicist Robert Garayev (a former member of one such group) singles out the marginalization of the 1960s-1970s generation, the destruction of the Soviet family institution that left tens of thousands of teenagers “cut off” from their parents. It was also the division of urban areas into ghetto neighborhoods with no public spaces-all while insisting that none of the local groups were formed along ethnic lines.[4]

The persistent image of crime capital was gradually changed to a multicultural one through republican propaganda—internal and external. Just as Vladimir Putin constructed the memory of the nineties, calling them “wild,” the state rhetoric of Tatarstan in the noughties was designed to cleanse the city's image of both the criminal and political legacy of the previous decades. There was also a building of the new Republic's image to attract tourists through self-exoticization. The most important milestone on this path was the grand celebration of the millennium of Kazan in 2005, the state commission for the preparation of which was personally headed by Putin. For the commemorative date, the subway and the Kul Sharif Mosque in the [Kazan] Kremlin were opened, and Yarmarachnaya Square was cleared up and renamed Millennium Square.

On March 21, 1992, Tatarstan held a referendum on the sovereignty of Tatarstan. The only question on the ballot was:

“Сез Татарстан Республикасының суверен дәүләт, халыкара хокук субъекты буларак Россия, башка республикалар һәм дәүләтләр белән мөнәсәбәтләрен тигез хокуклы килешүләр нигезендә урнаштыруы белән килешәсезме?”

“Do you agree that the Republic of Tatarstan is a sovereign state, a subject of international law, building its relations with the Russian Federation and other republics and states based on equal treaties?”

As a result of the referendum, about 60% voted in favor.

On February 15, 1994, presidents Mintimer Shaimiev of the Republic of Tatarstan and Boris Yeltsin of the Russian Federation signed an agreement, “On Demarcation of Competence and Mutual Delegation of Powers,” according to which the republic received the exclusive right to form the budget, manage land and resources (for example, oil), create its system of state bodies, its currency, participate in international relations and even issue separate citizenship. An essential point in the treaty was the declaration of Tatar as the state language. Also, the head of the republic, contractually referred to as president, was obliged to speak two languages: Tatar and Russian. After Vladimir Putin came to power, the policy regarding the exclusive status of the Republic of Tatarstan began to change—not for the better for the republican autonomy. In August 2000, Putin compared the inconsistency of federal and local laws to a time bomb that “must be removed and destroyed.” He used this same metaphor again in 2020, pointing to the right of the Soviet republics to secede from the Soviet Union, a right enshrined in the Soviet constitution—a right that, according to Putin, was the precondition for its collapse, “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century.”

In the early years of the existence of the Russian Federation, when the rules of interaction between the new federal center and the regions were just being established, the main trump card for preserving the special status of the republic was a strong nationalist movement, a significant part of which demanded complete independence [of Kazan from Moscow]. The movement was based not only on separatist slogans but also on public sentiment, as evidenced by independent outside sources. For example, American historian Robert M. Geraci, who has worked in the Kazan archives since 1991, describes "how churches, mosques, and religious organizations are reopened, how pre-revolutionary ethnographic and religious books are republished, how multiple circulation historical journals are created, how a congress uniting Tatar diaspora representatives from around the world is established, how academic conferences are launched to seek new approaches and heated discussions of the nature of the Russian Empire and the ethnic history of the Middle Volga region.[5]

[5] Djerassi, Robert. Окно на Восток: Империя, ориентализм, нация и религия в России. [A Window to the East: Empire, Orientalism, Nation and Religion in Russia]. Новое литературное обозрение [New Literary Observer], 2013. p. 6.

Mintimer Shaimiev, the first president of the Republic of Tatarstan, managed to use the domestic political situation for his purposes. His office maintained the impression that without Shaimiev's leadership in Tatarstan, the ethnic conflict would flare up, which positively affected the rating of the republic's president. Thus, even despite the corruption scandals that followed, Shaimiev gained the image of a “good patron,” which is reflected, for example, in his nickname, known to most Tatarstanis—Babai.

According to “nation-building in post-Soviet Russia” researcher Carine Clément, this situation allowed Tatarstan to exert pressure on the federal center and conduct largely independent policies for over a decade. In these years, balancing between the “federal” scenario and separatist sentiments has become the de facto basis for political stability and the only successful strategy that the republic's presidential apparatus has staked on. Jerasi writes: “Tatarstan <...> resisted the temptation to define itself in ethnically narrow and exclusive terms—instead its leadership emphasized the fundamental legitimacy, inevitability, and even maximum desirability of diversity. [6] The intermediate results of this policy are also reflected in Clement's sociological study she conducted in Kazan: most respondents welcome what they call “multiculturalism” or “multinationalism,”[7] but at the same time local Russian nationalists are much more xenophobic towards other (non-Tatar) ethnic groups and migrants.[8]

Over time, Tatarstan's “multicultural” ideological model—the peaceful coexistence of different religions and ethnic groups—is firmly entrenched in everyday life. In Kazan, it is challenging to meet ads for rent with the specification “only Slavs” (or vice versa, “only Turks”). However, the main goal of this model is to regulate relations between Moscow and Kazan and to demonstrate “peaceful coexistence” between the Tatars and the Russians. This clearly indicates, for example, the attitude of the republican authorities to “Хәтер көне”— the Day of Remembrance of defenders of Kazan, fallen in the capture of the city by the troops of Ivan the Terrible. In recent years, the local prosecutor's office does not allow public events marking the Khater Kona. Their participants are fined and detained. The ideological construction of Moscow-Kazakhstan relations cannot be called a trend of recent years; it has been going on since the collapse of the USSR. For instance, when Boris Yeltsin visited Kazan in August 1990, the local people asked him for help with issues related to their sovereignty and national identity. In fact, the relations between Russians and Tatars, was indicated. Interestingly, it was during this speech that Yeltsin, addressing the citizens of Kazan, uttered the famous phrase: “Take as much sovereignty as you can swallow.”

Labor migration in modern Kazan

There is a contradiction: on the one hand, the republic's leadership is proud of its policy of multiculturalism, while on the other, it only uses it as a “safety bag” to regulate relations with Moscow. The hypocrisy of official discourse is most evident in migration policy.

In early February 2022, Deputy of the Kazan City Duma Alfred Valiev wrote a letter to the Prime Minister of Tatarstan, Alexey Pesoshin, and Chairman of the State Council, Farid Mukhametshin. In his letter, Valiyev points to numerous complaints about problems with migrants and proposes a tightening of migration policy. According to the text of the appeal, party representatives claim that crime is growing among migrant workers. The latter allegedly despise Russian culture, mores, customs, and morals. According to party members, “citizens from Transcaucasia and Central Asia, who know neither Russian laws, nor the state language, live according to their traditions and customs.”

Such initiatives are publicly and unspokenly supported “from above,” sometimes emphasizing the contradiction outlined earlier. So, the current President of the Republic of Tatarstan, Rustam Minnikhanov, simultaneously allows himself to make public racist statements—and at the same time, when asked about the reasons for the rise in housing prices in Kazan, blames it on a sharp outflow of migrants. When asked about the integration of migrants in the “hospitable republic,” Minnikhanov answers with a suggestion to “sort wheat from the chaff,” meaning that the republic “needs educated, literate, normal people” who “should not feel like migrants” and deserve to receive “all kinds of support.” The question is who these “normal people” are and how they differ from other migrants.It is also interesting here how Minnikhanov indirectly points to federal acts that exist to regulate migration because, in his opinion, the influx of illegal migrants, “crooked migration,” is a threat to the whole country: “They have come to visit and are here somewhere on a sabbath.” Thus, Minnikhanov ignores the clauses of the 1994 treaty, which, among other things, provides for own policy on labor migration.

New comments on the video of Minnikhanov's speech about migrants appear regularly, and a significant number of commentators share the opinion of the head of the republic. One user, who introduced himself as a Tajik, writes of his surprise that he is being expelled from Tatarstan. In Tajikistan, his neighbors, were Tatars, and he has always been very sympathetic to them, especially when he moved to Tatarstan. In contrast, Moscow and the Russians made a very different impression on him: “I wasn't tired at work, I was mentally tired of the Russians on the way to the store—such words and nasty things I heard. I served in Afghanistan. An Afghan was kinder than a Russian—they shoot at you, you can die, but you won't hear a nasty word, and you have peace of mind.” The user adds that he is glad the USSR collapsed and that he was able to see what kind of people actually live in the Moscow region.

To present the official discourse demanding that state institutions take action, we also turned to informants experiencing the migration experience. One of them, Zukhra, fled the revolution in Tajikistan, managed to live in Moscow and Kazan, and now lives with two daughters in the city of Zelenodolsk:

“There are a lot of migrants from different places in Moscow, and the acceptance is not warm. Here, in Kazan, the attitude is entirely different. The difference is big. You don't feel so alien in Kazan. They treat you with understanding. In Moscow, some people treat you well and say hello, while others, like your flatmates, won't even respond to a greeting. All in all, the attitude of the person to newcomers is very different. I am a Muslim, and everyone in Kazan treats this normally. In Moscow, if you go into the subway wearing a hijab, someone might sit further away from you or say something nasty to you. I have made a lot of friends and acquaintances in Kazan. We meet, communicate, and visit each other. And in Moscow, people don't visit each other, for one thing, there's no time, you don't live there at all. You work, exist, and that's it. There's a rush and noise; no one pays attention to anyone. Well, here I live for my pleasure, and also I earn.”

“I'm very blond myself. I look like a Tatar, and in Moscow, women always came up to me and said, ‘Are you a Tatar?’ They also see me as a local, and Tatar women address me in Tatar. And I answer in Russian because I'm afraid to say something rude and wrong.”

Zuhra also shares her daughter's experience:“She didn't speak Russian before—she could watch cartoons in Russian, but she couldn't speak fluently. When we went to school, we tutored her, we read books, and she could read, write letters and speak a little bit. Now she speaks Russian more or less, but she has mistakes in prepositions a little bit. She's in first grade now and once said, ‘Nobody plays with me’.” I understand why: she sometimes gets her words wrong, and the kids probably aren't comfortable playing with her. They play, but they have no close friends yet—well, they probably don't understand, but that's normal for first grade. I say, “Next year, you'll have a close friend.”

“It's not any easier for the kids here. She understands that we want to stay here. She says: ‘No, my homeland is Tajikistan. I want to go to Tajikistan. I have no friends here.’”

All of the above confirms sociologist Evgeni Varshaver's idea that the slogan of Russian state policy could be formulated as follows: “We need compatriots and those who can easily integrate into Russian society.” We should also take into account migrant society in big cities and regional centers. At the same time, in smaller communities, the efficiency of diaspora ties is higher—in a small space, it is easier to build relations. For example, Zukhra says that it was in Zelenodolsk that she made friends with girls from Kyrgyzstan who had already obtained Russian citizenship and helped each other, for example, with finding jobs.This story is a personal, extra-institutional case of mutual aid. Today we cannot find independent grassroots initiatives to support Zukhra and her daughter. We are talking about organizations that are looking for ways to integrate migrants into Russian society, such as “Children of St. Petersburg,” “Civil Assistance,” “Migrant Children” or “Equally different,” “Tong Zhakhoni,” “PSP-Foundation”. Nevertheless, today there are at least three pro-state organizations operating in the republic, whose activities officially assisting migrant workers: ACNO “New Century,” the Federation of Migrants of Russia in the Republic of Tatarstan and the House of Friendship of Peoples.

The New Century organization is involved in administrative matters at the state level: it provides legal assistance, develops an appendix for migrants, receives large grants for this, and works directly with the government of the Republic of Tatarstan. Our informants nor we were able to assess the productivity of this organization. We also were not able to talk to their representatives.The Federation of Migrants works directly with the objects of migration policy. Among other tools, the federation has a chat room where migrants can ask questions about migration laws, medical care, and finding housing and jobs. During the lockdown period, chat participants helped women with children as the least protected class. Mobilization is being actively discussed in this chat right now:

“Hello, please tell me, those with residence permits—can also be drafted into the mobilization?”

“No, foreign citizens will not be engaged for mobilization unless they want to.”

Russian human rights activists tell of some cases of migrants being forced to sign contracts for voluntary military service—by deception or physical violence. In this sense, the moderator of the chat room of the Federation of Migrants of Russia in the Republic of Tatarstan reproduces the propaganda of the government of the Russian Federation, distributing only “official” information. The organization also prints a newspaper in Moscow—but not for migrants, just for a statistics. In Russian, it presents recent events held by the organization in the regions, such as charitable aid or the “Miss FMR” contest, which aims to “introduce viewers to the multinational diversity of the fair sex living in Russia, with their national traditions and customs, expand cultural ties between peoples, strengthen friendly and good-neighborly relations.” This contest is an amazing precedent for embedding migration into the quasi-multicultural logic of the [Moscow] Kremlin.

Finally, the House of Friendship of the Peoples of Tatarstan is an institution of integration inherited from the Soviet system, which was given second birth in Kazan in 1999. In 2005, Mintimer Shaimiev signed a decree, according to which the House of Peoples' Friendship became an independent organization, subordinate to the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Tatarstan, and financed from the republican budget. Shortly after the decree was signed, the house premises were distributed among the ethnic communities of the republic. According to one informant, the activities of these communities ranged from migration service functions (in the case of Uzbek representatives, consultation, and assistance with documents) to the creation of “islands of identity preservation” through a cultural program. The House of Friendship of Peoples of Tatarstan also publishes the magazine “Our Home is Tatarstan” in Russian.

1 (033), February 2015

According to our data, all three organizations described above do not cooperate. All of their activities and reporting are based on building relationships with the leadership of the Russian Federation or the Republic of Tatarstan. Analyzing their actions, we can draw a simple conclusion: despite the potential attractiveness of the republic for migrants, the leadership of Tatarstan has focused on reproducing the type of “multiculturalism” policy described in the previous section of this material—focused primarily on relations with the federal center.

Is Tatarstan for Russians? The limitations of “multiculturalism” policy

In addition to the Soviet national discourse of “friendship of peoples,” there is also a far-right anti-migrant discourse, “Russia for Russians” in the Russian Federation. The perception of migrants by Russians is mobile, it is complicated by the constant presence of “foreign Russians”—“non-Russian” ethnicities designated as a whole, whose cultural, geographical and historical differences are often ignored and reduced to generalization and search for universals (e.g. “friendship of peoples”).

The insistent appeal to the “Russian” identity as the only legitimate one is carried out not only “from below”—in marginal far-right circles but also “from above” at the level of imperatives promoted in the bureaucratic and managerial sphere. For example, the idea of “one nation, one culture, one state,” which by default erases all distinctions, is voiced directly by the first person of the Russian state: “I am Lakec, I am Dagestani, I am Chechen, Ingush, Russian, Tatar, Jew, Mordvin, and Ossetian.” The president of Russia erases the boundaries between the concepts of “Russian” and “Citizen of Russia,” offering a choice without any alternative: a citizen of Russia automatically means Russian. “We are all Russians,” as one propaganda video bluntly puts it. Of course, there is no question of equality here—the population is obliged to silently identify with the “state-forming,” universal identity. Such a national policy assumes a four stage construction, where the “state-forming nation” is located at the top, below—other “recognized by state” ethnicities, which appearance can be defined as “Slavic” or “Caucasian.” Lower—Russians, who are labeled as “non-Russian,” and at the very bottom—migrants, “non-Russian non-Russians.”

The hierarchical attitude towards different ethnicities, from “whiter” to “less white,” is the legacy of the national policy of the Russian Empire and, at the same time, the policy towards “national minorities” in the USSR. It included the division of territory, the transformation of language, forced resettlement, the universal and generalizing (hence erasing differences) concept of “Soviet” man, etc. The modern approach also follows the logic of this hierarchy, which has adopted the Soviet understanding of “multiculturalism.” It is already problematic in its very origins, not only in Tatarstan but also in the neighboring republics and many other geographies of the Russian Federation.

Such a “step-by-step” construction hardly contributes to good neighborliness and integration development. Examples include the numerous “folk” festivals that imply identification with one's ethnic category under the slogan “We are different but equal” and other initiatives built on bringing everyone to a universal signifier. It also takes no account of people's personal experiences or historical and/or sociopolitical contexts. Such initiatives force one to identify with one of the nations represented “on the list” and to compete to fit into an already existing hierarchy at the political level. A non-white person can only compete with other non-whites (often migrants) to become “equal” or “close” to those who are on a higher step—white, imperial.

Ignoring the organizers' context can be inappropriate (as in the case of the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize and the presentation of the laureates as “Slavic brothers”) and potentially provocative. Here we can recall the mass fight between Azerbaijanis and Armenians near RUDN at the “Moscow Made Us Friends” festival after announcing the results of the competition.

Kazan spends significant funds annually to maintain the “multicultural capital” brand. Meanwhile, events introduced into Kazan's public spaces often follow the same [exoticizing, emphasizing universal commonality, and ignoring context] logic. Financial support was provided, for example, for the open-air exhibition about the peoples of Tatarstan, installed on the square in the center of the city. This project not only reproduces ethnic stereotypes by superficially presenting various ethnicities as something foreign and alien in a few strokes, but it also completely ignores the historical reasons for their “close intertwining” within the same geography, simply placing everyone on a “common” plane of public space.

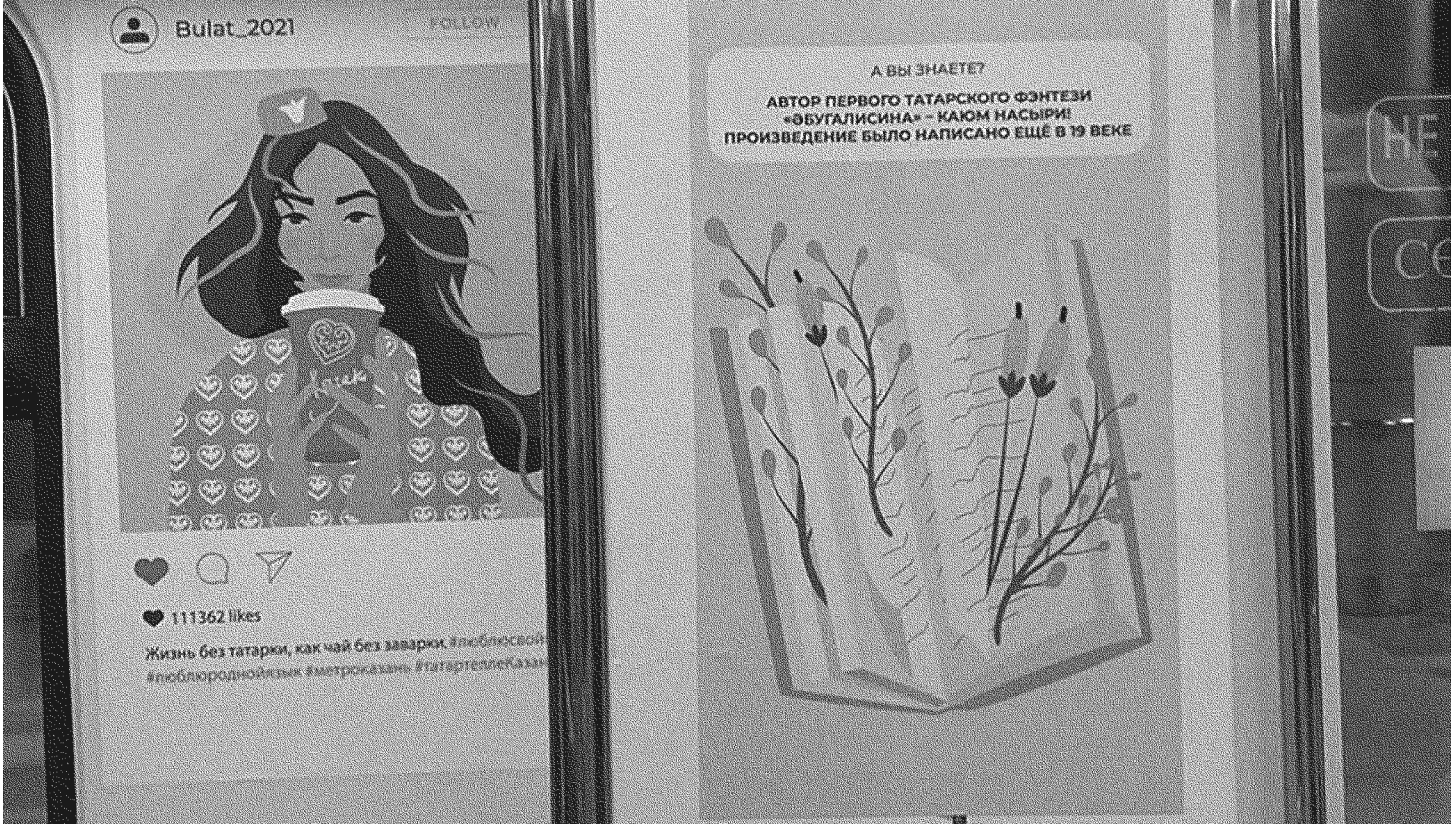

Another initiative that fits the description above is the “Native Language Train.” It ran in the fall of 2021 in the Kazan subway and was a train of six cars, ornamented with national and ethnic symbols, conversational phrases, and popular expressions in different languages. At the same time, the narrative was arranged hierarchically. The main focus of attention was directed to “our” and only then to “someone else's.” In some illustrations it is especially noticeable that the “Tatar” is not thought of by the authors as something independent and autonomous—only in an ironic way or in the binary opposition “Tatar/Russian.”

Other ethnicities outside the two “main” ethnicities are presented in the same problematic way. Looking at the cars dedicated to different ethnicities and languages, it is as if the city dweller becomes a social observer and looks at migration problems “from above” through a certain lens-rhetoric, without noticing the hierarchy built on top of it, as well as their narrowness of view and inattention. It leads to a negative attitude. Such disregard under the guise of “peaceful coexistence” and “multiculturalism” is openly demonstrated by the project itself. For example, the numerous mistakes made in the inscriptions in different languages. It is enough to say that the project's authors mixed up Georgian and Armenian languages. Interestingly, mistakes were corrected by native speakers of the languages used in the project right in the car—with markers.

This kind of “multiculturalism,” which grew out of the heavy ideological and political inheritance of the Russian Tsardom, the Russian Empire, and the USSR, does not create ties but destroys them. It does not include members of different ethnicities in society, at best only capturing the current state, however, fragmented it may be. An alternative might be an intercultural approach that transforms the usual “our-others” relationship by referring to the stories of individuals, their families, friendships, and other ties, necessarily taking into account historical and political contexts.

However, some contemporary Russian institutions are trying to adopt this approach with varying success. For example, the exhibition of Yakut artists “Save laughter for winter…”. The team of curators worked with all the participants individually, taking into account their personal experiences—this is a relatively positive example. The same cannot be said about the Second Caucasian Biennale of Contemporary Art with the “Descended from Mountains” declared theme. Even in reinterpreting imperial tropes, this is a reproduction of the relationship between colony and metropole.

One example of an intercultural approach to events in Tatarstan is the exhibition “I am not a stranger here,” held at the Museum of Islam in the Kazan Kremlin. It was devoted to the problems of migration processes and whether it is possible to use Kazan and Tatarstan's “multicultural” potential to make the relationships of people from different places safe and comfortable. The main preparatory work for the exhibition was done by anthropologists from the Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, who recorded personal stories of migrants and presented them in one space. Thus, an in-depth introduction to the personal stories of people with migration experience was intended to reduce the distance between visitors to the exhibition and the characters of the stories, to help them realize the similarity of these stories to ours.

However, according to some informants, the exhibition did not quite live up to its name: “I'm not a stranger here—it's about me in the collective, the museum staff, the museum in the Kazan Kremlin, and the Kremlin in the city. Can anyone say for themselves that they are not strangers here?” In the absence of integrative social institutions, under conditions of a strict ethnic and national hierarchy, first-generation migrants, including participants in the exhibition “I am not a stranger here,” acutely feel their unsettlement. The brand of “multiculturalism” is an empty signifier for them, bringing no advantages to anyone but populist bureaucrats. Our respondent, one of the exhibition organizers, partly agrees with this.

An example of horizontal structure and the “individual-individual” relationship can be seen in the curatorial work at the Kunsthalle Tenst by Maria Lind. People with migrant backgrounds and artists work in the same space: “That is the nature of contemporary art: to see people and what they live by.” The problem is that an entirely different kind of relationship is practiced on the territory of the Russian Federation and its constituent entities. It is based on “state-group” or “group-group”. In this kind of relationship, reinforced by propaganda narratives about the “friendship of peoples,” people's histories are erased, and their characteristics are unified. Each person is allocated a socially acceptable role in terms of power. Such a system does not allow new, non-Soviet practices to fully develop, turning into a populist machine whose cynicism deprives enthusiasts of motivation.

“The national policy of Tatarstan in a sense can be called multiculturalism, but it requires reservations,” one of the exhibition organizers, “I am not a stranger here,” agrees with our theses during a personal conversation. “I'd like to do projects like this in a more private format, where participants can talk quietly to each other without engaging in loud public relations activities involving the media. [In that way] I don't want to get involved in this anymore.”